'A lost generation': How austerity has created vacuum being filled by drug gangs exploiting children

Exclusive: 'Where public services have shrunk there’s a vacuum, and what’s stepped into it is gangs'

Austerity and rampant drug dealing have created a “lost generation” of children living in fear of violence across the UK, police and former gang members have said.

There are fears the recent spate of bloody street stabbings in London, where 20 teenagers have been killed so far this year, will not be the last if funding to police and public services is not urgently increased.

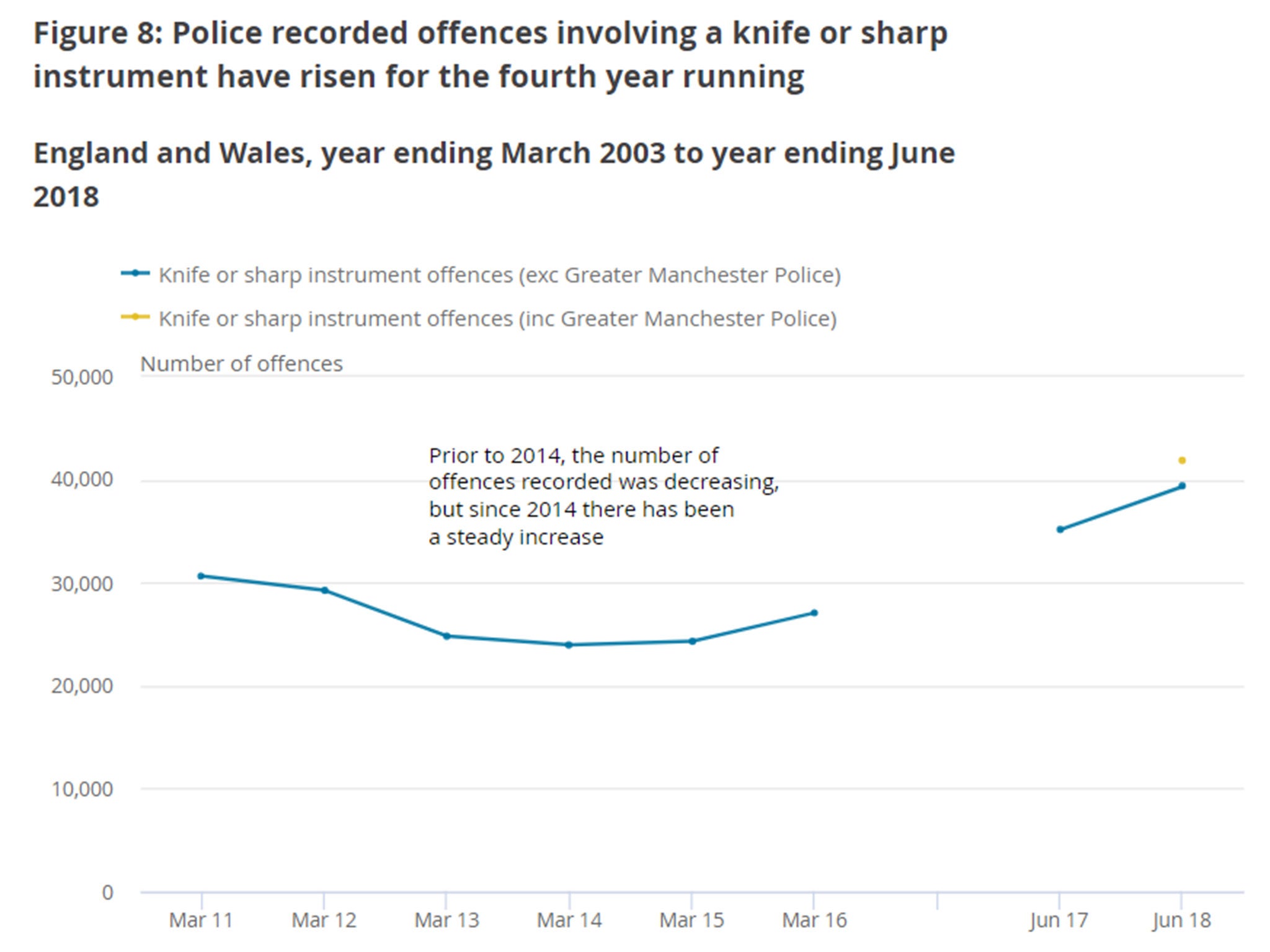

Knife crime stands at a record high, but Home Office-funded research has found that authorities in many areas do not understand how gangs operate or how social media is fuelling violence.

And statistics show that the rising number of people found carrying knives and being stabbed are getting younger and younger, with nine-year-olds “tooling up” in the mistaken belief that it will protect them.

Mark Burns-Williamson, chair of the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners, said children were being exploited by “county lines” – gangs that export drugs and violence from urban to rural areas.

He told The Independent the problem was being exacerbated by school exclusions and the closure of youth centres and other services aimed at keeping teenagers off the streets.

“If we’re not careful, we’re building up a generation of young people who are going to be lost to the system,” Mr Burns-Williamson said.

“It is a real worry and we have to look at early intervention and prevention.

“The government has come very late in the day to this, we know we can’t just turn these things around overnight. It takes a lot of sustained work upstream to really make a difference.”

Gavin McKenna, a former gang member who now runs the Reach Every Generation group, said he was seeing children involved in gang culture and drug crime getting a lot younger.

“Often the most worrying and violent kids are 12 to 14,” he told The Independent. “There’s a whole generation getting taken out because nothing has been done to stop it.”

Mr McKenna said austerity was fuelling knife crime, with violence starting to increase in 2014 as government cuts took their toll.

“Youth clubs are missing, there’s no safe place in their communities to go,” he said. “When I was young [in the 2000s], even when I was up to no good, it was a place where you could go and nothing would happen.”

Following the loss of more than 20,000 police officers since 2010, he said that vanishing neighbourhood police had left a perception that they only turned up when there was a problem and then no one would talk because there was no trust. “Communities feel alone,” he said.

Mr McKenna said the government should award long-term investment to grassroots organisations that could engage with affected groups, but warned: “You can’t just throw money at a problem.”

Anti-violence groups are targeting primary schools, rather than secondary, in attempts to show children the reality of gang life before they are drawn in by promises of money and protection.

A recent report found that some children are starting to deal drugs to provide for their families, while others are drawn into debt bondage and controlled by violence and intimidation.

The pattern is frequently seen in county lines dealing, where gangs use branded phone lines to target towns and rural areas, flooding them with drugs and controlling the lucrative supply.

Children are used to carry drugs to regional bases, which are often taken over from vulnerable people, and sometimes to deal – putting them at risk of robbery and stabbings by rivals.

The Violence and Vulnerability Unit, an organisation supported and commissioned by the Home Office, found that in most areas of Britain, no one could really explain or understand the local drug markets and how they were driving violence.

Programme director Simon Ford said the business model was expanding to areas being targeted for the first time, and believed that many more lines were running than the 1,500 identified by authorities.

“They will travel extensively to set these markets up because it’s so lucrative,” he told The Independent.

“Gangs will move kids around across the UK from one area to another …they’re disposable to them; if one gets arrested or killed, somebody else can come in.”

Mr Ford said the trade had normalised knife carrying for drug dealers, while children in the areas where they operated were arming themselves in fear.

“I think we’re in the worst of it at the moment and I don’t know how long it will continue,” he said. “It’s not going to be a quick fix.”

He agreed that the UK was risking a lost generation, explaining how children were becoming traumatised and did not know how to escape their situation, with some growing up to become gang elders and exploit younger teenagers in turn.

“Before they would speak to youth leaders and offending workers,” Mr Ford said. “They don’t talk to people any more because they’re so frightened about what’s going to happen to them.”

He said that where austerity had caused the shrinkage of public services – including youth offending teams, youth clubs, housing officers and social workers – there was a vacuum and what had stepped into it was gangs.

“Young people feel abandoned and they see the gangs as a form of protective service,” Mr Ford said. “They’ll befriend them, give them money, give them gifts, security and friendship. Very quickly that turns into debt bondage and they’re made to work.”

Sheldon Thomas, founder of the Gangsline charity, said some children came to see gang leaders as father figures and became attracted to their lifestyle through social media.

“When I was in a gang it was unheard of to recruit children because we had morals,” he told The Independent. “We didn’t believe that a 10-year-old should be selling drugs on some 20-year-old gang member. Morals and values are missing and that’s a societal problem.”

He called on the government to fund more programmes that sent people with “lived experience” of gang crime into schools, where pupils could relate to them.

A Home Office spokesperson said £1bn more was being spent on policing than three years ago and its National County Lines Coordination Centre was a key part of the strategy to tackle violent crime.